Outcomes Of Anterolateral Spine Exposures Done By Vascular Surgeons For Vertebral Osteomyelitis

Harleen K. Sandhu, MD, MPH1, Mitchell Benton, MS12, Karl Schmitt, MD3, Charles C. Miller, III, PhD4, Kristofer M. Charlton-Ouw, MD5.

1McGovern Medical School, UTHealth, Houston, TX, USA, 2University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR, USA, 3McGovern Medical School at UTHealth and Memorial Hermann Hospital at TMC, Houston, TX, USA, 4McGovern Medical School at UTHealth, Houston, TX, USA, 5McGovern Medical School at UTHealth and Memorial Hermann Hospital at TMC, HOUSTON, TX, USA.

Introduction:

Vascular surgeons often assist with thoracic and lumbosacral anterolateral spine exposures. In cases of vertebral osteomyelitis, placement of antibiotic-impregnated polymethylmethacrylate (AI-PMMA) cement can act as both spinal support spacer and an antibiotic carrier. We present our single-center experience with anterolateral spine exposures for vertebral osteomyelitis.

Methods:

We retrospectively reviewed cases of anterolateral spinal surgery and identified those with infectious indication. A composite variable of persistent infection or death was created. Data were analyzed by contingency table and multiple logistic regression.

Results:

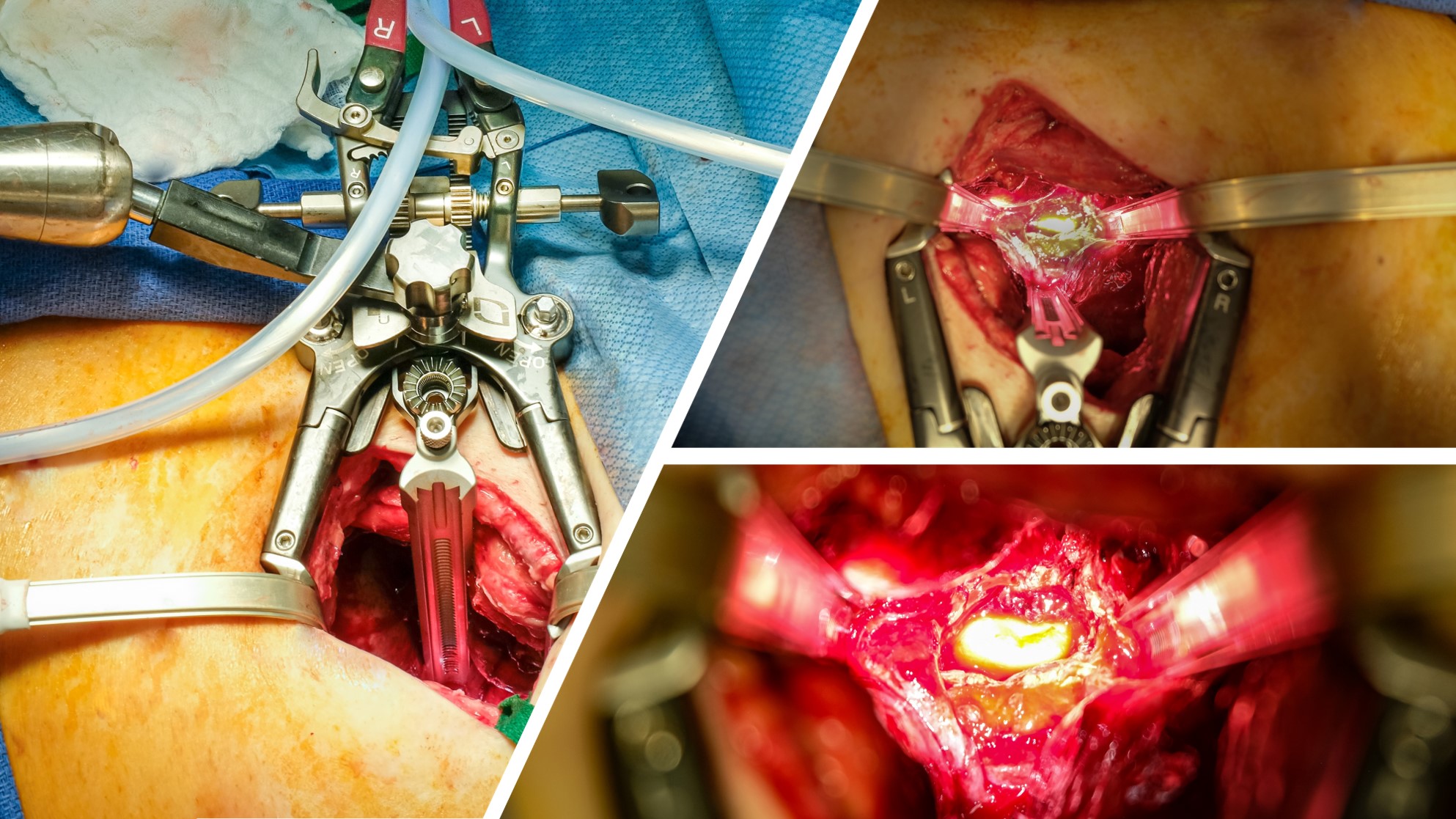

Of the 38 truncal vertebral osteomyelitis cases, 24 were thoracic (63%), 6 were lumbar (16%) and 8 involved both regions (21%). 13 were treated with AI-PMMA (Fig.1). 27/38 had at least one preoperative culture, and 19 of these had positive surgical site cultures. The most common organisms were gram positive (34%), with 13% gram negative, 5% anaerobes, 5% fungal and the remainder polymicrobial. No vascular complications were observed in AI-PMMA group with 1 in non-AI-PMMA group. Compared to non-infected cases, median intraoperative time (106 vs 128, p<0.27) and blood loss (664 vs 750ml, p<0.47) was not significantly different. Postoperative complications were not different between infected and non-infected cases, except for pulmonary complications (21% vs 6%, p<0.02). There was no early mortality in the non-infected cohort (24% vs 0%, p<0.001). Median follow-up time for the VO cohort was 11.8 (IQR:4.2-15.4) months. 7 patients were lost after discharge (N=31 remaining). 17/31 (55%) were clear of infection at clinic follow-up, 5 (16%) had persistent infection and 9 (29%) died. Composite outcome was 5/9 (56%) in the AI-PMMA treated vs 9/22 (41%) in those receiving other types of bone graft (p=0.693). Among those with active infection, composite outcome was 3/6 (50%) in those treated with AI-PMMA and 5/9 (56%) in those receiving other grafts (p=1.0).

Conclusion:

In a small sample, the efficacy of AI-PMMA is difficult to evaluate, but VO exposures have similar operative times, blood loss, and in-hospital complication rates compared to non-infected exposures. Access surgeons should be familiar with techniques and outcomes of VO exposures.

Back to 2020 ePosters