Racial And Ethnic Differences In 5-year Outcomes And Imaging Surveillance Following Elective Endovascular Repair Of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Christina L. Marcaccio, MD, MPH1, Priya B. Patel, MD, MPH1, Livia E.V.M. de Guerre, MD1, Aderike Anjorin, MPH1, Jacqueline E. Wade, MD1, Peter A. Soden, MD2, Kakra Hughes, MD3, Marc L. Schermerhorn, MD1.

1Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA, 2Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI, USA, 3Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC, USA.

Objectives: Racial/ethnic disparities in perioperative outcomes following AAA repair have been described, but differences in long-term outcomes are poorly understood. Our aim was to identify racial/ethnic differences in 5-year aneurysm rupture, reintervention, survival, and imaging surveillance after elective EVAR and to explore potential mechanisms underlying these differences.

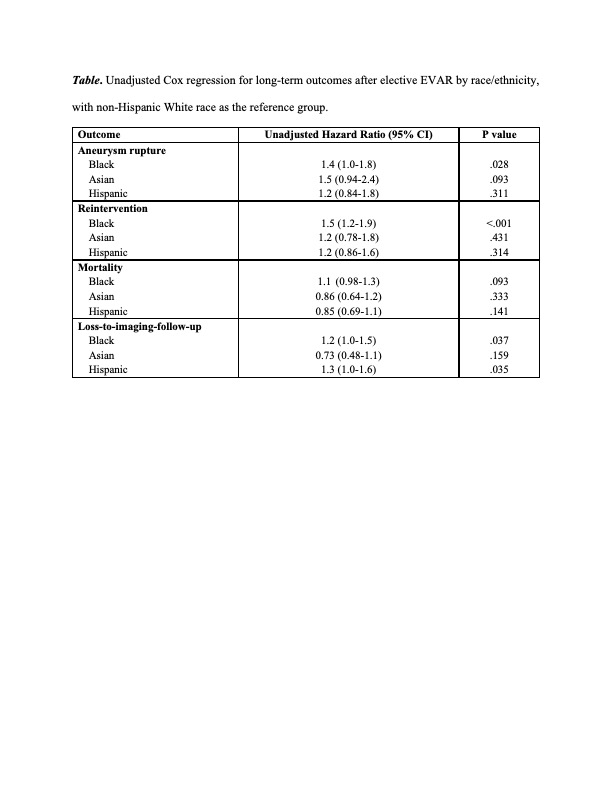

Methods: We identified patients undergoing elective EVAR for AAA in the VQI from 2003-2017 with linkage to Medicare claims through 2018 for long-term outcomes. Our primary outcome was 5-year aneurysm rupture. Secondary outcomes were 5-year reintervention and mortality and 2-year loss-to-imaging-follow-up (defined as no aortic imaging studies from 6-24 months after EVAR). We used Kaplan Meier and unadjusted Cox regression analyses to evaluate these outcomes by race/ethnicity and then performed an adjusted analysis to explore potential contributing factors, including procedure year, demographic characteristics (age, female sex, hypertension, smoking history), anatomic characteristics (AAA diameter, concomitant iliac aneurysm), environmental factors (hospital/surgeon volume), and loss-to-imaging-follow-up.

Results: Among 16,040 patients, 14,655(91%) were non-Hispanic White, 592(3.7%) were Black, 33(2.1%) were Hispanic, and 175(1.1%) were Asian. At 5 years, rupture rates were 14% in Black patients, 13% in Asian patients, 12% in Hispanic patients, and 9.9% in White patients. Compared with White patients, rupture rates were higher in Black patients (HR:1.4/95%CI:[1.0-1.8]/p=.03) but similar in Hispanic patients (HR:1.2/95%CI:[0.84-1.8]/p=.31)(Table). Low numbers prevented meaningful assessment of rupture in Asian patients (HR:1.5/95%CI:[0.94-2.4]/p=.09)(Table). In addition, Black patients had higher rates of reintervention (5-year: 27% vs. 18%/HR:1.5/95%CI:[1.2-1.9]) and loss-to-imaging-follow-up (2-year: 19% vs. 16%/HR:1.2/95%CI:[1.0-1.5]) but similar mortality (5-year: 39% vs. 37%/HR:1.1/95%CI:[0.98-1.3])(Table). Hispanic patients also had higher loss-to-imaging-follow-up (2-year: 20% vs. 16%/HR:1.3/95%CI:[1.0-1.6]) but similar rates of reintervention (5-year: 19% vs. 18%/HR:1.2/95%CI:[0.86-1.6]) and mortality (5-year: 30% vs. 37%/HR:0.85/95%CI:[0.69-1.1])(Table). In adjusted analyses, the association between Black race and 5-year rupture remained significant.

Conclusions: Compared with White patients, Black patients have higher rates of 5-year rupture and reintervention after elective EVAR. Both Black and Hispanic patients have higher loss-to-imaging-follow-up after elective EVAR, and thus may benefit from improved clinical outreach efforts. A larger-scale investigation of current practice patterns and their impact on racial/ethnic disparities in late outcomes after EVAR is needed to identify tangible targets for improvement.

Back to 2022 Karmody Posters